Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

History of Sfakia - part 2

At the crossroads of traffic between Europe, Asia and Africa

ROMAN PERIOD (67 B.C. - 330)

In 67 BC, Crete was conquered by the Romans after two years of siege. This was followed by a period of peace during which the cities, Gortys being the capital, flourished. Luxurious roman buildings, temples, stadiums and baths were built. The population by then was numbering 300.000 inhabitants. The biggest cities were Knossos, Cydonia, Aptera, Ierapetra, Phaestos, Littos and Eleftherna. The presence of Romans did not influence the daily life and habits of Cretans who retained their language and worshipping customs. This is the time when Crete first heard about Christianity and the first church was founded by Agios Titus, the islands' protector saint and apostle Paul's student. In 330 AD, after the roman empire was divided in the eastern and western parts, Crete became part of Byzantium.

From 'Travels

and Researches in Crete', Vol. II, Captain Spratt, London 1865

St. Pauls ship caught in the Euroclydon storm (Meltemi); Mt. Ida and

Paximadi islands in the back

PROTOBYZANTINE PERIOD (330 - 824)

The Byzantine Empire's history officially commences with the founding of Constantinople in 330 AD by the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great. Crete was governed by the Romans as part of the administrative imperial unit of Illyricum, as the southern part of the Balkan peninsula was known. When the Roman empire was divided in 395 AD, during the last days of the emperor Theodosius the Great, Crete became part of Byzantium.

During this period Christianity was spreading rapidly throughout both the Eastern and Western parts of the old Roman Empire. Despite the fact that the administrative control of Crete was from Constantinople, the control of the archdiocese of Crete remained under the see of Rome, with the exception of a short period after 476 AD when Rome was taken over by the Visigoths, until 754 AD when finally it was brought under the church of Constantinople. Many churches were built in Crete during this time with more than 40 early Christian churches having been uncovered by archaeologists to date. Some of the biggest churches of the island were the basilica of Agios Titus in the area of Gortyn, the basilica of Panormos near Mylopotamos and the basilica of Almyrida Apokoronou.

The first three centuries of this period were quite unusual for Crete in that they were peaceful years, although the island was hit by a number of severe earthquakes, one of which in 415 destroyed Gortyn, and the plague afflicted the island quite frequently. But from the middle of the seventh century the Arab pirate fleet started attacking the coastline and islands of the Byzantine Empire with Crete becoming a regular target. The Byzantine fleet was ineffective in protecting its coastal territories and these attacks intensified during the eighth century with the eventual control of the island falling to the Arabs in 824 AD.

ARAB RULE (824 - 961)

The Arabs that took control of Crete in 824 AD were Saracen Arabs from Cordoba in Spain led by Abu Haffs. They were forced out of Spain by the Moslem rulers of Andalusia around 813, and after seeking a new home in Egypt and capturing Alexandria in 818, they were again expelled from there and were forced to seek a new home and that's how they eventually arrived in Crete.

They were initially just a few thousand only, but due to the decline of Byzantine military presence in Crete, they eventually managed to take control of the whole island although this conquest occurred over a period of time. They soon established a new fortress surrounded by a deep trench (Chandax) which soon became the capital of the new Arab state at the location of today's Heraklion and it was from here that the conquest of the whole island took place.

Although there are no significant instances of resistance or rebellion of the population during this period against the Arabs, there is evidence that significant parts of the island never experienced the Arab rule, and one of those areas was Sfakia. The mountainous areas of Sfakia provided the safety needed by all those that managed to escape from the coastal plains and it was only the Sfakian villages in the south that experienced regular harassment from Arab raiders. During this period an unusual form of self-government emerged in Sfakia, the Gerousia, with its members, the Gerontes or Dimogerontes, selected by general consensus by the members of the community. This form of self-government has continued in Sfakia over the centuries but its influence today has been reduced considerably.

During the Arab rule, Byzantium tried to take back Crete initially in 825-826 AD under General Photeinos and in 826 AD, General Krateros caused severe casualties to the Arabs, but he was eventually defeated, captured and executed. A third campaign soon after also failed. Numerous further attempts failed until Nikiforos Phokas, a general with proven experience in dealing with Arabs, was appointed to the task of recapturing the island. A huge force was put together, numbering possibly over one hundred thousand soldiers, carried there by a large fleet, and after a protracted period of fighting Chandax fell on 7 March 961.

Large numbers of Sfakian warriors joined General Phokas who, during the siege of Chandax, appointed them to guard his rear from possible attacks from the south while he concentrated on Chandax. The Sfakians not only defended his troops from attacks from the south but also many joined the siege of Chandax and the general's gratitude and admiration for their contribution was shown later through presents of weapons, ammunition and lavish clothing for the Gerontes. He also gave them the right to continue with their own form of self-government and exempted them from all taxes.

When Phokas became Emperor a couple of years later he reconfirmed these privileges he had given previously to the Sfakians.

NEOBYZANTINE PERIOD (961 - 1204)

The second Byzantine Period begins with Crete' liberation by Nikiforos Phokas on the 7th of March 961 after 147 years of Arab rule.

The country had been devastated by the Arabs and many of its inhabitants had been sold as slaves in the slave markets of the east. The economy was in ruins and the administrative structure of government was non existent. The Byzantines immediately started rebuilding the fortifications of the island to guard against future attacks, introduced a new administrative organization dividing the island into a number of provinces and appointing their own governors.

Thus began a new period of cultural and economical renewal and the revival of Christianity in Crete. Missionaries spread the word of Christianity again around the island which was so affected by the 147 years of Arab Muslim rule; two of them were Saint Nikon 'Metanoite' ("Repent") and Saint Ioannis Xenos. The local population grew and to further assist the Emperor Alexios Komnenos the first, ordered the migration and settlement of Byzantine families in Crete around 1080.

This administrative arrangement and the new Byzantine settlers does not appear to have worked successfully because one hundred years later under Emperor Alexios Komnenos the second, grandson of the first, an imperial order was issued appointing 12 princes from Byzantium to govern Crete and gave each an extensive area to own and control, thus dividing Crete into 12 separate areas. Each prince, known as 'Archondopoulo', arrived with his extended family and settled in the area allocated to him. From this event, a number of great aristocratic families of Crete emerged, some of them still in existence today.

Sfakia was allocated to Marinos Skordilis, nephew of the Emperor who came together with 9 of his brothers and sons and their families. His territory's borders were from Askyfou east to Koustogerako, and along the south coast to Agia Roumeli, Omprosgialos (today's Chora Sfakion) and to today's Frangokastello. The largest town in the centre of this area was Anopoli and there are a number of ruins in the area that are attributed to the Archondopoulo and his family. A large number of today's Sfakian families also claim to be direct descendants of the original Skordilises.

Ioannis Phokas, a direct descendant of the General who freed Crete from the Arabs and later on became the Emperor Nikiforos Phokas was considered to be the most senior amongst the twelve Archontopoula. His territory was one of the largest ones, covering the greater part of today's Nomos of Rethymno, all the way south to the coast and West up to the valley of Askyfou, where the border of the Skordilis territory was. The name of the family changed a few years later under the Venetians to Kallergis and families that today claim to be direct descendants of the Phokas / Kallergis dynasty are one of the largest family groups in Crete, including a number from Sfakia.

While the new order under the Archondopoula was settling-in in Crete, two separate events were unfolding to the north of Crete that would eventually result a few years later in Crete being taken away from Byzantium for ever. In Rome Pope Innocent the third who ascended the papal throne in 1198 immediately proclaimed an other Crusade. And in Constantinople the decline of the Byzantine Empire had commenced in 1180 following the appointment of a very young Emperor, Alexios Komnenos the second, who was deposed a couple of years later, followed by a very unstable period that saw three new Emperors over the next twenty years.

The Fourth Crusade eventually got ready to sail out of Venice in November, 1202, under funded and in heavy debt to the Venetians who provided the fleet to transport them to the Holy Land. But at the same time, Alexius, the son of the recently deposed and blinded Byzantine Emperor Isaac Angelus, negotiated with the leader of the Crusade, Marquis Boniface of Montferrat, that if the Crusaders were to escort him to Constantinople and enthrone him there, he would part finance the Crusade and also give them an additional 10,000 soldiers to assist them in capturing Egypt.

In the end the Crusaders after enthroning him but not being paid, attacked and took over Constantinople in April 1204, and as part of the sharing of the spoils of war, Crete was allocated to Boniface. Boniface who did not have the means to take control of the island accepted an offer from the Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, and sold Crete to Venice on the 12 August 1204 for what was seen at the time the very small amount of 1,000 silver marks.

VENETIAN RULE (1204 - 1669)

The Venetian Rule began with the occupation of Constantinople by the Franks of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 and the sale of Crete by the Marquis Boniface of Montferrat to the Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo on 12 August 1204. In addition to Crete, and in accordance with the treaty the Venetians had with the Crusaders, they got control of the western coast of the Greek mainland and the Ionian islands, all of Peloponnese, Euboea, Naxos, Andros, the main ports of Hellespond, the Thracian seaboard and the city of Adrianopole, as well as part of Constantinople. Thus the Venetians emerged as the main beneficiaries of the overthrow of Byzantium by the Fourth Crusade, having secured the crossroads of trade in eastern Mediterranean.

Venice was not prepared for such a big expansion and became preoccupied by problems it encountered in Peloponnese and the Aegean, and was unprepared to take full control of Crete. Its Genoese long term enemy, Enrico Pescatore, Count of Malta, took the opportunity to move onto Crete, where not only he did not encounter any resistance from either Venetian troops or the local inhabitants, but he was even assisted by Cretans who were bitter about the fall of Constantinople and the sale of the island to the Venetians. Soon he was able to take control of large parts of Crete and commenced fortifying Chandax, Rethymnon and Siteia and other parts of the island.

The Venetians soon sent additional troops and commenced with their attempt to push the Genoese out of the island. Numerous battles were fought during the next few years and eventually the Venetians managed to take full control of the island in 1212, although some smaller parts remained under Genoese control until 1217.

During the next 420 years and until the Ottoman Empire commenced with its campaign to take over the island from the Venetians, the Cretans rebelled against the Venetian rule no fewer than 27 times, without counting any other smaller local uprisings. Some of those revolutions lasted for years and were eventually suppressed by the Venetians with great brutality. Many of these revolutions sprang out of the Lefka Ori or the White Mountains, the stronghold of Sfakia. Many of them were led by members of the Archondopoula families, and especially members of the Sfakian based families of Skordilis and Kallergis. But before looking at some of the more noteworthy of these revolutions and their brutal suppression, a brief look at the military, religious and administrative controls and taxes over the island’s inhabitants will assist in better understanding why this remains the most torturous period in the history of Crete.

In order to take firm control over the island Venice started resettling numerous noble families from Venice, starting in 1212 and continuing with this resettlement over the next few decades, resulting in about 10,000 Venetians moving to Crete by the end of the century, representing about one sixth of the population of Venice. Chandax was renamed Candia (today's Heraklion) and became the seat of the Duke of Candia, appointed for a two year period by Venice, and the island became known as the Regno di Candia, the Kingdom of Crete. During the same period, in 1252, Chania was built on the site of the ancient city of Kydonia. Crete was divided into six provinces ('sexteria'), and, later, in four counties, but Sfakia remained out of the direct control of the Venetians who maintained only a small garrison at the castle at Omprosgialos (Chora Sfakion today), who rarely ventured out of their castle walls.

Military control

One of the first activities that the Venetians embarked was to build fortifications throughout the island and form a readily mobile army that could quickly move and attack the latest insurrection. Venetian nobles were obliged to maintain war horses and armour and make themselves and a number of soldiers available to fight uprisings, when requested by the Capitano di Candia or the Proveditor General who were in command of the army.

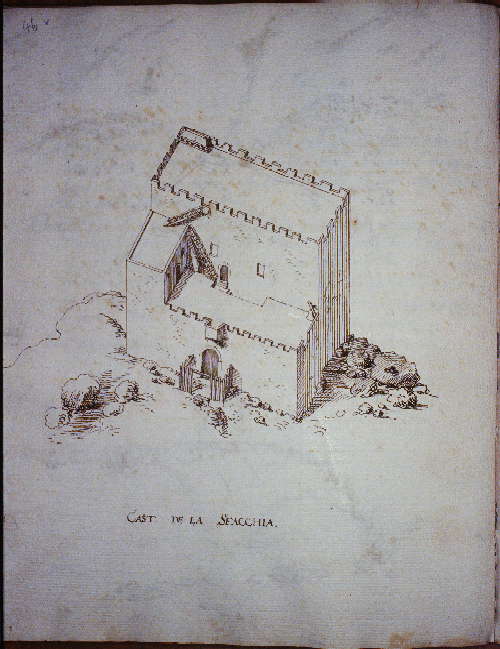

Venetian drawing of 'Castel de la Sfacchia', 1621

The fortifications built during the Venetian period can still be seen throughout Crete, at Heraklion, Rethymno, Chania, Souda, Kasteli, Gramvousa, Spinalonga, Sitia, Ierapetra, Sfakia, and many others. They were built through the compulsory labour of both men and women who were conscripted from lists of those liable to compulsory service which were maintained at each village.

One of particular interest from a Sfakian history viewpoint is the Frangocastelo at Sfakia. The Venetians who were experiencing ongoing incursions on the south coast of the island from pirates, some of whom were Sfakians, and to protect the Venetian nobles and their properties decided to build a castle on the fertile plains east of Sfakia where they intended to locate a strong army contingent. The castle would also protect them from the Sfakians who lived in the mountains north and west of the plains and who also were harassing the Venetian nobles. A Venetian fleet with soldiers and builders arrived there in 1371 and they started the construction of the castle, but the local Sfakians who were against such a castle in their territory, with the leadership of the 6 Patsos brothers from the nearby settlement of Patsianos, were destroying every night what the Venetians and their builders were building during the day. Eventually the Venetians were obliged to bring additional troops that surrounded the whole area during the whole period while the castle was being built.The Patsos brothers, who were betrayed, were arrested and hanged at the site of the castle. The building of the castle was eventually completed in1374 but the Sfakians were never threatened in their stronghold by the Venetian troops who were stationed there and who preferred to stay in the castle looking out for pirates rather than try and bring any control over the Sfakians.

The Navy remained under the control of the Admiral of the fleet of Venice, the Capitano General da mar, but a large number of Venetian ships were stationed and maintained in Crete where significant facilities were built, some of which are still in existence today in both Chania and Heraklion, known as the Arsenali.

Thousands of Cretans were conscripted annually to man the hundreds of Venetian galleys as rowers, each ship requiring about 200 to 240 rowers. Many died due to the abhorrent conditions, drowned as the ships sank, were killed during battles that the Venetians fought and many more were captured by pirates and sold in the slave markets of the east, never to see Crete again. The impact of this contribution to the Venetian maritime supremacy in Cretan human lives was reflected in part in the reduced numbers of the inhabitants at the end of the Venetian rule.

The Church during the Venetian rule

The closeness between the state and church in Crete under the Byzantines was something of great concern to the Venetians who although Catholics, were at a distance in their relations with Rome. For them Venice and its interests were paramount and the interests of the Catholic church came a distant second. Immediately they set themselves to break up the unity that they observed in the Cretan relationship of the people and their church. And they started this process by removing all the Orthodox clergy and banning the visit of any Orthodox priests to the island. At the same time they encouraged Catholic monastic orders to come to the island to proselytise and convert Cretans to the catholic faith and appointed a Catholic Archbishop in charge of the church in Crete from one of the wealthy families of Venice. A new order of Orthodox priests was created to head the Orthodox church in major population centres, known as Protopapades (head priests) who were of the Uniate faith, i.e. Orthodox in favour of amalgamation with the Catholic church and who conducted services alongside Catholic priests.

This situation continued until the later part of the 16th century and resulted in considerable deterioration of the influence that the Orthodox faith had over the population of the island. Moral standards fell, both within the clergy but also throughout the Christian community and many conversions for opportunistic purposes took place. The only areas that managed to maintain Orthodoxy and its strict moral standards were the few Orthodox monasteries on the island that became the bastions of Byzantine Orthodoxy.

Towards the end of the 16th century and as Venice started becoming concerned about the threat of the Ottoman Empire, they started becoming more tolerant towards Orthodoxy on the island with the hope of gaining an ally against the possible invasion of the island by the Ottomans.

Administration and Taxes

A centralised administrative control similar to that in existence in Venice was immediately installed in Crete. A large number of bureaucratic layers were established manned by newly arrived Venetians responsible for all matters relating to law and order, tax gathering, imports and exports, ship berthing, storage, and all other activities that the new state saw as necessary to extract maximum benefit from its new acquisition. Substantial salaries were being paid for all this bureaucratic machinery making it imperative that a regular guaranteed tax income stream is maintained.

Property previously belonging to Cretans that offered any resistance was allocated to the new Venetian nobles, together with all buildings, animals and furnishings belonging to any villagers living on those properties, who were considered as slaves. The new Venetian owners were liable to taxes on the produce generated on their properties as well as the maintenance of military horses, armour and the provision of fighting men whenever they were requested to do so. The Cretan nobles that did not resist the arrival of the new order were allowed to keep their properties but faced similar taxes, but were not required to contribute to the fighting capacity of the new state as only Venetians were allowed to be members of the army. Head taxes and other revenue raising mechanisms were imposed upon the population, some of them arbitrarily by nobles that wanted to raise their own level of income. Soon a tax farming system emerged where rights to tax gathering were being sold to higher bidders who were prepared to pay amounts that would guarantee them the ability to raise taxes over and above those required by the state. A large number of the revolutions were triggered by extortionate levels of taxes as villagers reached to the point where life was not worth living any more as nothing was left to them to sustain life for themselves and their families.

The problems created by the very hight level of taxes and associated corruption was a matter of concern to Venice who twice sent commissions of inquiry, the first in 1413 who reported back of nobles plundering the population and tax gatherers pocketing one third of all tax collected while a second one in 1574 similarly pointed out that the continuing unrest and never-ending revolutions reflected the extreme exploitation of the farming population.

As an example of a reaction to the heavy taxation regime it will be mentioned here only in passing that one of the revolutions in Crete was by the Venetian nobles themselves against Venice. Having complained at length about the oppressive levels of tax they decided to rebel when Venice imposed an additional tax in 1363 to upgrade the port of Candia. They arrested the duke and his officials and declared Crete a new state, the Republic of St Titus, in honour of the patron saint of Crete. Less than twelve months later the revolution was put down by a large force of mercenaries that Venice gathered and sailed to Crete.

Revolutions against the Venetians

As mentioned previously during the first 420 years of Venetian rule there were no less than 27 revolutions by the Cretans, not counting smaller local insurrections and other resistance activities. Some of these revolutions lasted quite a few years, and Western Crete and the Sfakian district was where quite a few of them started and the Archondopoula families and their descendants featured prominently in most of them. As mentioned above, most of them reflected the extortionate level of taxes and the brutal treatment the Cretans were receiving from the Venetian occupiers.

Here we will provide details of only three of them who were more colourful from a Sfakian historical viewpoint. But as Sfakia was considered an ungovernable and unconquerable district, these revolutions did not have the tax as the prime motive as far as the Sfakians were concerned.

The Chrysomalousa revolution

One revolution that occurred in 1319 was typical Sfakian in its nature, as it involved honour and pride, and was contained in the Sfakia district alone. The garrison which the Venetians maintained at Omprosgialos at Sfakia, consisted of only 15 soldiers and an officer, who were keeping an eye on the Sfakians but rarely ventured outside and never interfered with what was going on in the area. One day the officer in charge, Capuleto, attracted by a young girl at the well of the village approached her and kissed her. She slapped his face but he pulled his dagger and cut some of her golden hair. Her name was Chrisi Skordili, (Chrisi = Golden) from the Archondopoula family of Skordilises, known by all as Chrisomalousa, the Golden hair girl, due to her blond hair. Immediately her relatives killed the offending officer and most of the guards. Venetian troops arrived soon from Chania and the locals fought the Venetians bravely throughout their district. The revolution went on for more than one year, until finally through the intervention of Archondas Kallergis, who at the time had reached a peace treaty with the Venetians, agreement was reached for the withdrawal of the Venetian forces from the area and an end to the hostilities.

The war of the chickens

An other revolution that was sparked by a typical Sfakian reaction to an increasing pressure by the Venetians to extract additional taxes from the long suffering Cretans occurred in 1470 and has remained known in Cretan history as the 'Ornithopolemos' or the war of the chickens. A new tax was introduced requiring all Cretan families to provide one well fed chicken every month to the Venetian in charge of their area. As time went by and families multiplied, the number of chickens demanded was increasing and arguments started about what the correct number should be. Some villages started giving eggs rather than chickens on the basis that the Venetians could hatch the eggs themselves instead! Legal action was taken by the Venetians against the villagers for short payment as well as against the Sfakians who were refusing to pay this tax all together and more than 10,000 indictments were issued. The Sfakians in return compiled a report charging the Venetian authorities of corruption and sent the report to Chania for despatching to Venice. The authorities at Chania imprisoned the Sfakian who brought the report and that got the Sfakians to declare a revolution and encouraged the rest of the Cretans to refuse the tax. The revolution and the fighting lasted for three years and at the end the Venetians agreed to withdraw the tax from the whole island and also withdraw all outstanding legal actions.

Kantanoleon's revolution and the Cretan weddings

This revolution has become part of the Cretan mythology

since the publication in 1872 of a book, 'The Cretan weddings' by

a Cretan writer and historian, Zambelios. The full historical

events have never been proven but

there are Venetian records that substantiate large parts of the story but they

do not fully explain why the wedding was proposed in the first place and by

whom.

The protagonists of this revolution that took place in the Western part of

Crete in 1527 (or 1570 according to an other source) are George Kantanoleon,

from the small village of Koustogerako, just north of Sougia, his son Petros,

Francesco Molino, a Venetian noble from Chania and his only daughter Sophia.

Although Kantanoleon came from Koustogerako, a small village just outside today's

Sfakia eparhia, this was on the border of Archondopoulo Skordilis Sfakian territory.

Kantanoleon was also from the family of Skordilis, some sources also claim

that his correct surname was Skordilis, and Kantanoleon was a name attributed

to him by the Venetians. Finally a large number of Sfakian families were involved

in this revolution, and that's why the Kantanoleon revolution is included

here as a predominantly Sfakian instigated revolution.

Some time before 1527, and in reaction to unbearable taxes and the brutal treatment of the people of the country, a large number of families of Western Crete decided at a meeting at the monastery of Saint John at Akrotiri to revolt against the Venetian rulers. There they elected George Kantanoleon as head of a new government. Following a number of successful battles against the Venetians at Impros gorge, Samaria gorge, near Rethymno and at Lasithi, the Venetians withdrew at Chania, allowing the new Cretan independent government total freedom in governing all Western Crete. Kantanoleon established his headquarters at Meskla at the foot of the Lefka Ori, about 15 km south of Chania and set up proper government processes including the collection of taxes, although at a more acceptable level than previously.

The events that followed are subject to debate. Zambelios, in his book claims that Petros, Kantanoleon's son, fell in love with Sophia, Molino's only daughter, and Molino conspired with the Duke of Candia to trap and exterminate all the revolutionaries by proposing and arranging for a marriage of his daughter and Kantanoleon's son at who's wedding all invited will be arrested and the protagonists of the rebellion killed. A Venetian historian, some time later in his version of events says that it was Kantanoleon that tried to impose a reconciliation between Cretans and the noble Venetian families of Western Crete by imposing the marriage of his son to Molino's daughter thus trying to establish a new dynasty to govern Western Crete. Where the two historians agree is in the events that followed.

At the wedding where a large number of Cretan guests were invited, following traditional festivities where large amounts of wine were consumed (spiced with opium according to Zambelios) all guests were surrounded by Venetian troops that came secretly from Chania, Rethymno and Candia, arrested Kandanoleon and his son and hanged them on the spot together with more than thirty other Cretan nobles. The rest of the prisoners, in their hundreds, were divided into four groups and one was hanged at the gates of Chania, one at Koutsogerako, one on the road from Chania to Rethymno and the fourth at Meskla, the headquarters of the rebel government. But the atrocities did not stop there, whole villages were destroyed including Koustogerako, Meskla, and a few others. Atrocities continued for some time and quite a few leaders and their families fled up in the mountains for some time until eventually an amnesty was given.

What has remained imprinted in the minds of Cretans for generations now is the fact that this was the closest they got to independence during the Venetian rule and that this taste for independence was taken away from them through treachery and the brutality that followed.

You can read more news about the history and archaeology of Crete on our History and Archaeology of Crete Forum